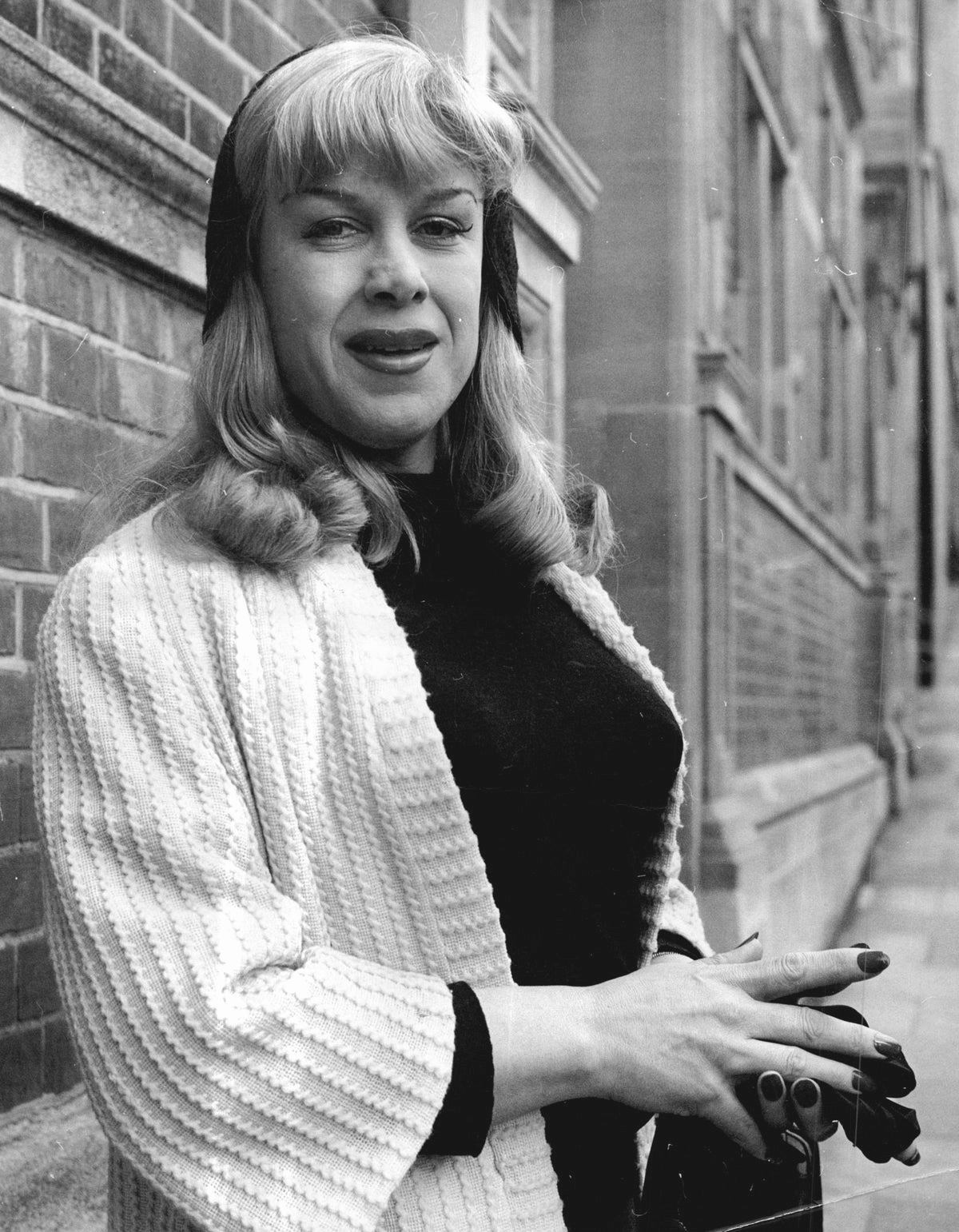

In 1951, Roberta Cowell began a transition in secret. Taking large doses of oestrogen while still presenting as a man. She then had her testicles removed, illegal in those days under the so-called ‘mayhem laws’. It allowed her to gain documentation that said she was intersex and allowed her to change her sex on her birth certificate to female. On the 15th of May, she became the first woman to have vaginoplasty in Britain, only ever previously carried out as an experiment on cadavers. Roberta changed her name on her birth certificate two days later. She would go on to have a long, healthy life, but one in which she became more and more isolated and, in the end, forgotten. But Roberta was no ordinary woman. She was a racing driver extraordinaire and a Second World War fighter pilot. She is a pioneer who paved the way for all trans women today to live the life they want to live. But when Roberta died, only six people turned up to her funeral. How could the life of a pioneer end so tragically? This is the story of her rise and her fall.

The Bravest Hero of the Wartime Fighter Pilots

Roberta Cowell was born Robert Marshall Cowell on April 8th, 1918. He was the son of Major General Sir Ernest Marshall Cowell KBE CB and Dorothy Elizabeth Miller. As a child, Roberta loved to travel, with photography one of her biggest passions. She was arrested in Germany once for shooting a cine film of a group of Nazis drilling. She secured her release by agreeing to destroy the film… but she didn’t.

She left school at 16 to join the General Aircraft Limited as an apprentice aircraft engineer but soon left to join the Royal Air Force, becoming an acting pilot officer on probation. She began pilot training but she was discharged because she got airsick. Around the same time, she also developed a love of motor racing, winning her class at the Land’s End Speed Trial in a Riley. She gained her experience sneaking into the area where the cars were serviced at the Brooklands racing circuit wearing mechanic’s overalls and offering help to any driver or mechanic who wanted it. By 1939, Roberta owned three cars and had competed in the 1939 Antwerp Grand Prix. But her famous racing career was soon to be interrupted by the arrival of the Second World War.

On December 28th, 1940, Roberta was commissioned into the Royal Army Service Corps as second lieutenant, serving in Iceland. She completed RAF flying training and served a tour with a frontline Spitfire squadron and then briefly as an instructor. By June 1944, she was flying with No. 4 Squadron RAF, a squadron assigned to the task of aerial reconnaissance.

She had an eventful career as a Spitfire pilot. Shortly before the D-Day landings, the oxygen system of her Spitfire malfunctioned at 31,000 feet over France. She passed out but the aircraft continued to fly, on its own, in a circle, for over an hour. It was bombarded by German anti-aircraft fire but it stayed in the air until Roberta regained semi-consciousness at a lower altitude. She was able to fly back to the squadron’s base at RAF Gatwick.

By 1944, Roberta was piloting one of a pair of Typhoons. She attacked targets on the ground but one day, her aircraft’s engine was knocked out and its wing was left badly damaged by German anti-aircraft fire. Roberta was an intelligent and skilled pilot. She was flying too low to bail out and instead jettisoned the cockpit canopy and glided her Typhoon to a successful landing. She was able to contact her companion by radio and confirm she was unhurt, but then she was captured by German soldiers.

She made two attempts to escape, but both failed. She spent several weeks in solitary confinement at an interrogation centre. She remained a prisoner for five months, spending most of her time teaching classes on automotive engineering to fellow inmates. But she was subjected to sexual advances by her fellow prisoners, making her feel uncomfortable. She was concerned that the other prisoners would see her as homosexual. Remember, she was still ‘Robert’, living as a man.

Conditions were tough. Roberta lost 50 pounds and had to kill and eat the camp’s cats. Raw. But salvation was coming. In April 1945, the advancing Red Army was approaching. The prisoners refused to leave. The Germans wanted to evacuate the camp but after negotiations, it was simply abandoned, leaving the prisoners behind. It was unguarded. Undefended. And now in the control of the Red Army.

Roberta was one of many flown back to the UK, left in a terrible state. But after her traumatic experience, she sunk into a deep depression and a growing discomfort with her body. In 1948, she abandoned her family, her wife and children, to seek help.

Little did anyone know what she was about to do.

The Deep-Rooted Distress and the Search for Identity

Roberta was in great distress. She offered suffered from flashbacks that panicked her, what we today would call post-traumatic distress disorder. She left her wife and sought out help from psychiatrists. Time and time again, they were of no help. Eventually, however, one psychiatrist told Roberta that her mind was ‘predominantly female’. She had been aware of her ‘feminine side’ all of her life, but she suppressed what she felt. She started to suspect the angst she was enduring was far more deep-rooted.

In 1950, Roberta began to take large doses of oestrogen but still lived as a man. She became acquainted with Michael Dillon, a British physician who was the first trans man to receive a phalloplasty. He wrote, as early as 1946, about how individuals should have the right to change gender and have the body they desired. The two became great friends.

It was Michael who performed Roberta’s inguinal orchiectomy, removing the testicles. This had to be done in secret as the procedure was illegal in the UK under the so-called ‘mayhem laws’. These were ancient laws that made it an offence against the person in which the offender violently deprives his victim of a member of his body, thus making him less able to defend himself. Although how you defend yourself with your testicles remains a mystery. No surgeon would operate openly on Roberta. After her secret surgery, she visited a gynaecologist and was able to obtain a document stating she was intersex.

It allowed her to have a new birth certificate and her sex changed to female. On May 15th, 1951, she underwent a vaginoplasty. The operation was carried out by the father of plastic surgery, Sir Harold Gillies, with the assistance of Ralph Millard. Vaginoplasty was very much in its infancy. Gillies had only ever performed experimentally on a cadaver. It was the very first time the procedure had been undertaken in Britain. And it was a success. On May 17th, Robert was gone. He had changed his name to Roberta. She was now a legally recognised woman.

Roberta was delighted with her transition, but she faced horrendous abuse in public for ‘not conforming to binary gender identification’. She also found it challenging to find work, with many places discriminating against transgender individuals such as Roberta and denying them work and opportunities. Her finances took a further hit when she was unable to continue racing, her biggest love, because the discrimination was too much to bear.

When we say Roberta was a pioneer, she truly was.

The Distant Memory of the Impossible Pioneer

Roberta owned her own racing car company and her own clothing company, a veteran of the Second World War regardless of her identity, but she was mistreated by the public and her business ventures collapsed. In March 1954, news of her gender reassignment became public and suddenly, everyone was interested in her. Many not for the right reasons.

In the UK, Roberta’s story was published in the magazine Picture Post. They gave Roberta £8,000 for her picture and story, and God, she really needed the money. She also published her autobiography shortly after, earning her £1,500. Meaning that in that one year alone, Roberta made, in today’s money, just over £225,000. Not too bad. But the public pressure on her was threatening to destabilise her mental health.

Roberta’s story caused a sensation in America. In 1952, the American public had become aware of the concept of changing sex because of Christine Jorgensen. The stories that made the newspapers, however, were often poorly written. They often conflated the concepts of sexual preference and gender identity, two concepts that are not related. In America, transgenderism became associated with homosexuality, a taboo in those days, and effeminacy in men. Roberta’s story confused people as it broke this narrative. She had served in the war. Spitfire and Typhoons no less. A star of motor racing, too. She was married to a woman and had children. Roberta confused the hell out of Americans. She was the epitome of perceived masculinity but now she was a woman. Roberta did not just challenge preconceived notions of gender, she changed them.

Her fame and notoriety, however, were short-lived. By 1958, Roberta was bankrupt. Her money had simply run out. The press almost delighted in her downfall. The Times, no less, ran headlines such as, ‘No Jobs for Miss Roberta Cowell’, revelling in her misery. She fell out of the public eye and the world forgot her.

The pioneer of transgender identity fast became a distant memory.

The Final Years of Depression and Solitude

Roberta was not finished, however. She continued to race motor cars, albeit not professionally. She was still active in British motor racing well into the 1970s. She also continued to fly. By the end of the 1970s, she had logged in over 1,600 hours as a pilot. An interview conducted at the time is often used as a stick to beat Roberta with. She reiterated she was intersex and spoke in disparaging terms of individuals who underwent male to female gender reassignment. Many believe criticising Roberta for this interview is unfair. She was at her lowest ebb. She was depressed again and had perilously little money. She was often confused and acted out of character. You can’t blame her for the things she said. She wasn’t herself anymore and most importantly, her gender reassignment, while bringing her much happiness at the start of her transition, had become the very thing that made people turn against her. She blamed herself. Her transition. Those that transitioned, too, and those that followed in her footsteps. Her blame was born of anger. I think that is entirely understandable, but that is not to say she was right to say what she said, of course.

Roberta moved into sheltered accommodation in the 1990s in London although she continued to drive large, powerful cars right into the 2000s. Remarkably, Roberta Cowell, a transgender pioneer, a life of heroism and tragedy, only died on October 11th, 2011. She was 93-years-old. Sadly, only six people attended her funeral and on her instructions, her death was not publicised. It was not reported until her obituary was published in The Independent in 2013. It was her only obituary in any newspaper until The New York Times published her obituary. In 2020.

Roberta was gone. There were no memorials. No statues. Nothing named in her honour. Not even her name taught in our schools. But she should be. She should have been celebrated. Instead, her story ended so quietly.

It was not what she deserved.

The Continual Fight for Recognition and Peace

Sadly, Roberta’s story is not uncommon. Many transgender people suffer abuse and are shunned from society, even to this day. Many have to fight hard for recognition and for the right to live openly as their chosen gender. Sometimes their fights are unwinnable, but it is in those darkest moments that those with a shred of decency need to rally around and support these marginalised communities. They can feel so isolated, so unloved. We still have so far to go. But Roberta is a pioneer. She helped to give transgender people visibility and helped transgender people transition. When certain authors criticise the transgender community, hashtags such as ‘Not In My Name’ are possible because of a legion of transgender pioneers empowering the future of the transgender community and giving them a voice, pioneers such as Roberta. Their voice is growing louder by the day. And Roberta really should be honoured and celebrated for her role in this history.

So why isn’t she? I think it is that interview in the 1970s. But that doesn’t take away the incredible life she lived. She was a racing driver and a hero of the Second World War. But the biggest challenge she faced was coming to terms with her identity and taking a leap of faith with her transition. Sadly, the reaction she received was painfully predictable. And painfully her name has been lost to history. But her transition definitely paved the way for trans women today to live openly.

She once told a friend, “I am not a eunuch, I am unique” and she was. Many will cast shade upon her for some of her decisions, including the choice to abandon her children and that infamous interview. But you know what? The amount of conflict inside her, conflicts that she battled with daily, are the battles those who are not transgender will never understand. Who are we to criticise her actions? She just wanted to live openly as a woman and God, she lost everything. She lost it all. No wonder she was angry.

That’s not how I choose to remember her. I choose to remember her relentless courage in the face of overwhelming hardship. That path she forged through the jungle for those who followed her. Her decision to live her own life on her terms as her true self is a deeply brave decision and bravery far greater than most will ever have to summon. She was a phenomenal woman. She took a huge risk and paid the price so others could live happily as their true selves.

She once said:

There seemed to be nothing to lose and a great deal to gain, both in future happiness and in scientific knowledge. Here was an opportunity for me to tread a path as yet untrod. Hopefully and fearfully, I started down the path.

March 31st is International Transgender Day of Visibility

The International Transgender Day of Visibility is an annual event dedicated to celebrating transgender people and raising awareness of discrimination faced by transgender people worldwide, as well as a celebration of their contributions to society.

Toodle-Pip :}{:

Post NC: Comments, Likes & Follows Greatly Appreciated :)

My Other Blogs: The Indelible Life of Me | To Contrive & Jive

Click Here for Credits (click on image to enlarge)

Post Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roberta_Cowell, https://chrysalisgim.org.uk/uncategorized/roberta-cowell/, https://www.ucl.ac.uk/campaign/roberta-cowell

Leave a comment