Food is a metaphor for living, so believed M.F.K. Fisher, real name Mary Frances Kennedy, born on July 3rd, 1908 in Albion, Michigan. Today widely regarded as one of the greatest food writers who ever lived, Mary radically changed the way we thought about food and taught all to love and appreciate what we eat. She had a knack of surprising people, spending her life behind the initials ‘M.F.K.’ so her gender was hidden, her lifetime of work considered ‘shocking’ in the 1930s for a woman to dedicate her life to. She wrote beautifully and confidently, writing about food convincing most that she must be a man, maybe a ‘frail young don from Oxford’, so her first publishers believed before they met her. For this, Mary became a trailblazer and in doing so, she changed the way we look at food forever…

From Albion

I was delivered at home by ‘Doc’ George Hafford, a man my parents Rex and Edith Kennedy were devoted to. Rex was then one of the volunteer firemen, and since I was born in a heatwave, he persuaded his pals to come several times and spray the walls of the house. My father Rex was sure I would be born on July 4, and he wanted to name me ‘Independencia’. My mother Edith was firmly against this completely un-Irish notion, and induced Doc Hafford to hurry things up a bit, in common pity.

– Mary.

Rex was co-owner, with his brother Walter, and editor of the Albion Evening Recorder newspaper, but in 1911, he sold his interest in the paper to Walter and moved his family to the West Coast, seeking a new life as a fruit or citrus orchard farmer. He nearly purchased an orange grove in Ventura, California, but problems with the soil forced him to back out. Eventually, he settled his family in Whittier, California, at 115 Painter Avenue. It was here in 1912 where he purchased a controlling interest in the Whittier News.

Rex never gave up on his dream, purchasing an orange grove on South Painter Avenue, the house sitting in 13 acres. It was known as The Ranch. Mary, meanwhile, was struggling in school, an indifferent student who often skipped class. Her parents enrolled her in a private school, but she constantly flickered from one school to another, never entirely settling, never entirely happy. It was her informal education that had a most profound impact on her. She met her first husband, Alfred Fisher, at UCLA, a school she dropped out of after one year to attend Occidental College, which she also dropped out of after one year to elope to Dijon in France with Alfred.

Mary loved to read and began writing poetry at just five, the vast home library a place in which she spent many an hour immersed in imagination. She even wrote for her father’s paper, sometimes as many as 15 stories a day. But food was her biggest passion in life and from the youngest of ages, she was committed to shaking the mould…

The Influences of Food

Mary’s earliest memory was the ‘greyish-pink fuzz my grandmother skimmed from a spitting kettle of strawberry jam’. Mary did not like her grandmother, describing her as ‘stern’ and ‘joyless’. She hated her bland, overcooked food. Whilst grandmother was away at various religious conventions, Mary recalled how:

[We] indulged in a voluptuous riot of things like marshmallows in hot chocolate, thin pastry under the Tuesday hash, rare roast beef on Sunday instead of boiled hen. Mother ate all she wanted of cream of fresh mushroom soup; father served a local wine, red-ink he called it, with the steak; we ate grilled sweetbreads and skewered kidneys with a daring dash of sherry on them.

Aunt Gwen was also an early influence on Mary, not family but the daughter of the Nettleship family, close friends of Mary’s family. They were a strange bunch of English missionaries who lived in tents on Laguna Beach, Mary often camping with them and loving to cook in the great outdoors. Her favourite was steaming mussels on fresh seaweed over hot coals, but she also loved to catch and fry rock bass, skin and cook eel, and making fried egg sandwiches to carry on hikes. It sounds awesome.

I decided at the age of nine that one of the best ways to grow up is to eat and talk quietly with good people.

– Mary.

Even as a child, Mary was constantly in the kitchen, cooking away. So she surprised everyone when, deeply in love with Alfred, she eloped to France. They settled at 14 Rue du Petit-Potet, an unbelievably, astonishingly beautiful street. The house, however, was far from ideal. Two rooms, no kitchen and no bathroom.

It hardly mattered for Mary. She was 22-years-old in one of the most beautiful parts of France with the love of her life. What more could you want?

The Love of Dijon

Alfred worked on his doctorate and when not in class, he was working on his ‘epic poem’, The Ghosts in the Underblows. By 1931, he had completed the first 12 books of the poem. Out of 60. He was a bit nuts. Mary, meanwhile, was attending night classes where she spent three years studying painting and sculpture. The home they rented in Dijon was owned by the Ollangnier family, serving good food. Mary later fondly remembered big salads made at the table, deep-fried Jerusalem artichokes and ‘rejected cheese’ that was always good.

To celebrate their three-month anniversary, Mary and Alfred, rarely apart, went to the famed Aux Trois Faisans restaurant where Mary received an education in fine wine from a sommelier she was rather fond of, a man named Charles. Mary and Alfred visited all the restaurants in town.

We ate terrines of pate ten years old under their tight crusts of mildewed fat. We tied napkins under our chins and splashed in great odorous bowls of ecrevisses a la nage. We addled our palates with snipes hung so long they fell from their hooks, to be roasted then on cushions of toast softened with the paste of their rotted innards and fine brandy.

– Mary.

She wrote her first book in the 1930s but used her initials as it was almost impossible then for a woman to be taken seriously as a writer, especially one writing about food. She believed that her first book, ‘Serve It Forth’, could only succeed if she fooled people into believing it was written by a man.

All this early success enabled Mary and Alfred to buy their own place at 26 Rue Monge, above a pastry shop, somehow an even more beautiful part of Dijon. She was living the best life, she really had landed on her feet. This is where Mary had her first kitchen, just five feet by three feet and containing a two-burner hotplate. It was here she started to develop her own style of cuisine. This was her origin story.

The moment she first donned the cape.

Something New

There in Dijon, the cauliflowers were very small and succulent, grown in that ancient soil. I separated the flowerlets and dropped them in boiling water for just a few minutes. Then I drained them and put them in a wide shallow casserole, and covered them with heavy cream, and a thick sprinkling of fresh grated Gruyere, the nice rubbery kind that didn’t come from Switzerland at all, but from the Jura… and was grated while you watched, in a soft, cloudy pile, onto your piece of paper.

Through these kinds of recipes, Mary aimed to shake her guests from their routines. But life was becoming hard for her. Alfred was spending more and more time away from her and, as such, Mary became depressed from loneliness and being cooped up in a cold, dank apartment. The couple moved around, Alfred grew more introspective and stopped working on his poem and eventually, Mary and Alfred’s wonderful time in France came to an end… their dream fizzled away and they returned to California.

Eventually, the couple settled in a cabin at Laguna, the camp now owned by Mary’s father on which he built a log cabin. This was the Great Depression and work was hard to find. Alfred spent two years looking for a teaching job whilst Mary continued to write. She worked part-time in a card shop and in her spare time, when she wasn’t writing, she researched old cookery books at the LA Public Library. She started to write short pieces on gastronomy, which formed the basis of her books. Publishers were keen, her professional life starting to take off, but her private life was disintegrating.

Her marriage to Alfred was failing and she started to have feelings for one of her friends: Dillwyn Parrish. She wrote at the time that she was starting to fall in love with him. One day, she sat by him at the piano and told him she loved him. In 1935, with Alfred’s permission, Mary and Dillwyn travelled to France and across Europe. Upon her return, she told Alfred how she felt about Dillwyn. Regardless, Mary and Alfred remained married.

Dillwyn invited Mary and Alfred to help him to create an artist’s colony at Le Paquis, something Alfred agreed to, despite the threat to his marriage Dillwyn posed. The house sat on a sloping meadow on the north shore of Lake Geneva. Mary loved the garden:

We grew beautiful salads, a dozen different kinds, and several herbs. There were shallots and onion and garlic, and I braided them into long silky ropes and hung them over rafter in the attic.

Inevitably, in 1937, Mary and Alfred separated. Alfred went on to become a distinguished teacher and poet. Mary later said that Alfred was afraid of physical love, he was sexually impotent and an intellectual loner. Ouch. It was a tumultuous time for her but her world was to change in an all-together different way in 1937.

Serve It Forth

Her first book, Serve It Forth, was published by Harper in 1937 and the reviews were glowing. Mary, however, was disappointed with the sales. She needed the money. Money problems were only exacerbated in 1938 when Dillwyn suffered clots in his left leg, eventually needing to be amputated. He was in constant pain for the rest of his life and the cost of his care was an enormous burden. He became very ill and there was no known treatment for his condition at the time. The couple eventually settled in California where the warm climate would be beneficial for Dillwyn. They settled in a small cabin on 90 acres of land near Hemet, naming it Bareacres. Mary wrote at the time:

‘God help us… we’ve put our last penny into 90 acres of rocks and rattlesnakes.’

Life was incredibly hard. Mary tried her best to get medicine for her husband, a man facing a future of increasingly agonising pain and multiple amputations. The medicine Dillwyn needed was not available in America. Mary petitioned to have the ban lifted on the drugs Dillwyn needed but his condition was getting worse and worse every day. She loved him so much, she fought so hard for him, for their future. But it wasn’t enough. Dillwyn was in a very bad place. And on the morning of August 6th, 1941, Mary was awakened by a gunshot.

Venturing outside, she found Dillwyn. He had killed himself. Mary did not know what to do. She had no money. She had lost the man she loved. And now she was all on her own in a barren land.

It was her darkest hour.

The Author’s Malaise

Desperately heartbroken, Mary threw everything she had into her writing. It was all she had left. She tried to publish a novel, but no publisher wanted it. She tried and failed again. Her third attempt, however, was a success. She completed and published ‘Consider the Oyster’. She dedicated it to Dillwyn. Considering what she had been through and the hardships she was facing, her book was humorous and informative. It contained recipes the likes of which nobody had seen before. People, for the first time, took notice of her witty one-liners and they started to fall in love with her exceptional talent.

‘An oyster leads a dreadful but exciting life.’ Consider the Oyster (1941).

The reviews were so good she decided to keep going. She published ‘How to Cook a Wolf’ in 1942, published at the height of the food shortages of World War 2. She told people how to achieve a balanced diet, stretch ingredients, eat during blackouts, deal with sleeplessness and sorrow, and care for pets during wartime. The book was critically acclaimed. It brought her success and a stint in Hollywood.

In 1942, she started working for Paramount Studios and it was here she wrote jokes for Bob Hope, Bing Crosby and Dorothy Lamour. In 1943 she became pregnant and during her pregnancy, she worked on her next book, The Gastronomical Me. She gave birth to Anne Kennedy Parrish on August 15th and gave the father’s name as Michael Parrish. She never revealed the true identity of the father.

‘We must eat. If, in the face of that dread fact, we can find other nourishment, and tolerance and compassion for it, we’ll be no less full of dignity.’

The Instructor

‘There is a communion of more than our bodies when bread is broken and wine is drunk. And that is my answer, when people ask me: why do you write about hunger, and not wars and love?’ The Gastronomical Me (Mary).

Mary never considered herself a food writer but a relationship that flourished in 1944 with publisher Donald Friede gave her access to additional publishing markets. She started to write articles for Atlantic Monthly, Vogue, Town and Country, Today’s Women and Gourmet. When Donald’s publishing empire collapsed, Mary and Donald moved to Bareacres to write. It was here in 1946 she gave birth to another daughter, Kennedy Mary Friede.

I accidentally got married to Donald Friede.

– Mary.

Mary worked on her next book, ‘With Bold Knife and Fork’, but when her mother died in 1948 she moved to The Ranch to take care of her father. On Christmas Eve, 1949, the release of Mary’s translation of Savarin’s ‘The Physiology of Taste’ received rave reviews. Craig Claiborne of The New York Times wrote:

‘[Mary’s] prose perfectly captured the wit and gaiety of the book and lauded the hundreds of marginal glosses that [she] added to elucidate the text’.

Despite this success, her marriage to Donald was starting to unravel. He became very ill and required considerable medical treatment, but it soon became apparent his condition was psychosomatic and he required urgent psychiatric care. All this put Mary under considerable stress having been Dillwyn’s carer and then losing him in such tragic circumstances. She weathered his suicide but then, one year later, her bother committed suicide and then, not long after, her mother died, only to find herself becoming the carer of her new husband and her father, who was so heartbroken when his wife died he could barely function. And Mary endured all of this with two young children to care for. Donald was so bad for her that he left her $27,000 in debt. Try $300,000 in today’s money.

For all the success of her public life, her personal life was one disaster after another.

The Breakdown

Inevitably, Mary sought psychiatric counselling for a nervous breakdown and it was during her counselling when Donald asked for a divorce. Poor Mary. You really feel so sorry for her. She was going through hell and the man who put her there had just walked out on her. Leaving her with all that debt. They divorced in 1950 but in 1953, tragedy hit Mary again when her father died. She sold The Ranch and his newspaper, renting out Bareacres and moving to Napa Valley.

Once more, she left America for France planning to live off what her father left her, seeking out better educational opportunities for her children. Life became one of routine. Each day, Mary walked across town to pick up her girls from school at noon and in the late afternoon, they ate snacks or ices. Mary was fed up. She never felt completely at home and felt as if the French were patronising her because she was American.

I was forever in their eyes the product of a naïve, undeveloped and indeed infantile civilisation.

– Mary.

One day, an important local woman, introduced to Mary through mutual friends in Dijon, invited her to lunch. The woman sneered at Mary, saying, “Tell me dear lady, tell me… explain to all of us, how one can dare to call herself a writer on gastronomy in the United Sates, where, from everything we hear, gastronomy does not yet exist?” The cheek.

It is, I think, impossible for people raised in our food-obsessed culture to understand the contempt Americans had for food and cooking when I was growing up. Newspapers of the 1950s banished food to the ‘women’s pages’… people who considered themselves gourmets were mostly men and rarely cooks… a suggestion that they would one day be celebrities would have been met with raucous laughter.

– Mary.

Mary moved back to America and sold Bareacres, buying an old Victorian house on Oak Street in St Helena. She moved around quite a bit in the 1950s, from Switzerland to Dijon and to San Francisco. She continued to be published, including a stint with The New Yorker. In her writings, food often served as a framing device, combining a signature mix of culinary, historical and sociological trivia, sprinkled with remembrances of her life and loves, her voice deep and distinctive.

The Last House

In 1971, David Bouverie, a friend of Mary, offered to build Mary a house on his ranch in Glen Ellen, California. Mary designed the home, one she called, ‘My Last House’. She continued to travel and write. After Dillwyn died, Mary considered herself a ‘ghost’ of a person but she continued to have a long and productive life. In her later years, she contracted Parkinson’s disease and started to suffer from arthritis. She spent her final two decades at the Last House. She died on June 22nd, 1992. She was 83.

Oh, she was the pioneer. She started the whole genre of food and memoir writing… she was the first, in this country anyway, to take food seriously in that way… [Mary proved that] you can be a serious writer and write about food.

– Barbara Haber (food historian).

Mary really was the first of her kind in America and completely changed the landscape of food writing and how people thought of food in the nation, challenging how food and health were perceived and becoming the template of all modern food writers. In her life, often defined by tragedy, tragedy she often overcame, she wrote 27 books and most received widespread, critical acclaim.

She hid behind the initials ‘M.F.K.’ to disguise her gender in a time when female writers, and especially female food writers, were not taken seriously, writing with supreme confidence and her famous wit. She made people care about food and in doing so, she forever changed the notion of what food writing could be and who could write it.

Mary Frances Kennedy Fisher was a pioneer, yes, but also a true trailblazer…

I do not know of anyone in the United States who writes better prose.

– W.H. Auden (of Mary).

Toodle-Pip :}{:

Post JV: Comments, Likes & Follows Greatly Appreciated :)

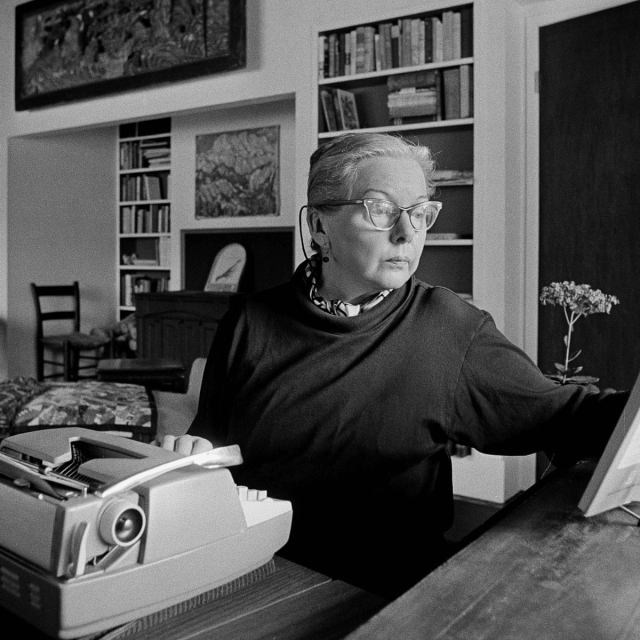

Image (click on it to enlarge): 1) Mary in 1971. Image Credit: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/oct/10/110-best-nonfiction-37-how-to-cook-a-wolf-mfk-fisher

Leave a comment